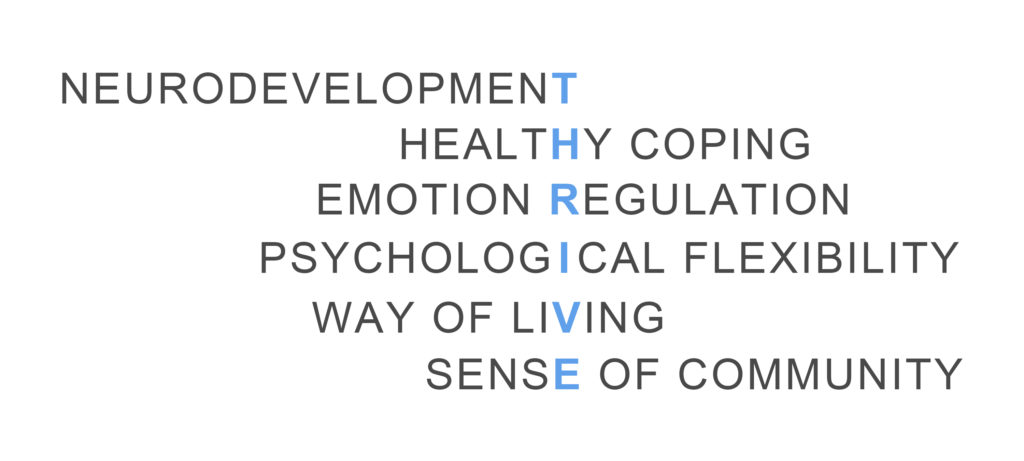

Overview of the THRIVE Sessions

The first—and most critical—program component are the five 90-minute psychoeducational sessions led by you, the program facilitator. Psychoeducation combines elements of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT), group therapy, and education and has become a valuable asset in the management of certain mental health issues, such as anxiety and depressive disorders[1]. The sessions will make participants more aware of the mental health impact of childhood adversity and introduce them to strategies and exercises that can help them strengthen their psychological resilience in the face of everyday and major life stressors.

A key focus of all sessions is to also provide participants with ample opportunity to apply the discussed concepts to their own life and personal experiences. According to some scholars, such a collaborative and needs-based learning environment tends to be most effective with adult learners[2].

The following will be covered in each session:

SESSION 1: The Neurodevelopmental Impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

In their first session, participants will learn that ACEs are a form of chronic stress that impact the development of the growing brain and body and over time may lead to neurobiological, emotional and cognitive dysfunctions (e.g., a dysregulated HPA-axis). It will also introduce participants to the diathesis-stress model[3], which explains in simple terms why childhood trauma puts survivors at greater risk for psychopathology and, hence, why managing one’s risk is critical. This information aims to reduce any stigma or sense of personal failure or shame related to mental health issues by drawing attention to scientific facts related to the brain, brain development, and physiological responses. It also aims to trigger an “Aha!” moment in participants, similar to the following survivor who in her late 40s said: “I always thought that I’ll get over it and move on at some point. After hearing you share this information I’m realizing that maybe I won’t. So maybe I need to address [my trauma] after all”[4].

SESSION 2: Healthy Coping

This is the first of three sessions that will introduce participants to different types of emotional and cognitive dysfunctions as well as strategies on how to address them. In this session facilitators will introduce ACE survivors to the concepts of healthy and maladaptive coping and allow them to apply the learnings to their personal experiences and life. First, the facilitator will discuss the differences between problem- and emotion-focused coping, active and passive coping, and controllable and uncontrollable events. Then, participants will have the opportunity to self-reflect on how they generally cope in stressful situations and consider how and when they could introduce or expand the use of the discussed healthy coping mechanisms. For “homework” participants will be asked to actively engage in a healthy coping strategy of their choice (e.g., calling a friend or summoning a meeting) in a commonly stressful situation (e.g., a stressful work assignment or family matter). This will allow them to expand the use of healthy coping strategies in their own life.

SESSION 3: Emotion Regulation

In the third session, participants will be introduced to the term “emotion regulation” and various emotion regulation tactics. The first exercise is called STOPP, which is an acronym that encourages people to stop, take a breath, observe, gain some perspective, and practice what works before proceeding in emotionally challenging or stressful situations[5]. The second exercise will introduce participants to three additional emotion regulation strategies, including practicing emotional self-awareness, fact checking emotionally triggering situations, and responding with opposite behavior. These emotion regulation tactics will show participants how they may get some distance from intense emotions and/or respond to them differently.

SESSION 4: Psychological Flexibility

In the fourth session participants will first learn about the concept of psychological (in)flexibility and cognitive dysfunction more broadly. This will be followed by two cognitive defusion exercises (a concept that is rooted in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)), which will allow participants to recognize and let go of thoughts, rather than get caught up in them[6]. During the first exercise, participants will be asked to close their eyes and let various unwanted emotions and thoughts pass by them in a “stream” of water[7]. Then, participants will partake in a cognitive defusion exercise that allows them to distance themselves from statements that are rooted in opinion rather than fact[8]. For example, they will move from statements such as “I’m an uncaring partner” to “I’m having the thought that I’m an uncaring partner” to “I notice I’m having the thought that I’m an uncaring partner”. This will allow participants to take a mental step back from such subjective (and often self-deprecating) statements. These and other mindfulness-based exercises can heighten the sense of self-consciousness and non-judgemental attention to current thoughts and experiences and have been found to positively impact psychological well-being and emotion regulation in ACE survivors[9,10].

SESSION 5: Lifestyle (Risk and) Protective Factors

The fifth and final session will focus on three lifestyle factors that are known to contribute to mental wellbeing: sleep, physical exercise, and social support. Prior to engaging in a discussion, participants will be asked to provide their self-perceived “health score” of each factor on a scale of 1-10, as well as provide their ideal (or target) score. The facilitator will then discuss research findings related to each factor which will be followed by the participants’ review of their ideal score for each factor and any adjustments participants see fit. Prior to closing the workshop participants will be invited to join an exclusive community of fellow participants for ongoing dialogue and support.

In addition to the above key concepts, each session will also provide opportunities for participants to engage in different types of mindfulness and breathing exercises.

In addition to the five sessions outlined above, your workshop participants will also be invited to join a private community of women ACE survivors. This community, which is hosted online, will allow program participants to stay connected, provide ongoing support to one another, and share resources. This program component is critical as social support—especially from individuals who can relate to one’s experiences—has been found to be a key protective factor for psychopathology following ACEs[11].

Last, but not least, program participants will have access to an extensive library of books, articles, videos, and more that build on the concepts discussed during the workshop. For example, some individuals may want to further explore mindfulness exercises or others may want to read more about certain neurobiological concepts. The library will also provide resources related to various evidence-based treatments, such as Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) or Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), and how to find a local counselor. Please contact us if you have any suggestions for other resources that could be added to the library!

You are greatly encouraged to also join the group, as it will allow you to stay in touch with your and connect with other program participants.

…